The drought in the western U.S. could last until 2030 - WBS Solar Pump

sourcehttps://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/the-drought-in-the-western-us-could-last-unti

publisherSimon

time2022/03/31

- After a brutally hot and dry 2021, the region is now in the worst "megadrought" in 1,200 years. Climate change is to blame.

After a brutally hot and dry 2021, the region is now in the worst "megadrought" in 1,200 years. Climate change is to blame.

There have been brief moments of reprieve in the drought that has stretched on since 2000 in the western United States—a water-rich 2011, a snow-laden 2019—but those breaks have only highlighted the more dramatic feature of the last few decades: unrelenting dryness.

Without human-driven climate change forcing Earth’s temperatures up, the ongoing drought would still be painful and parched. But it would be unexceptional in the grand scheme of the past 1,200 years. A new study in Nature Climate Change shows that Earth’s warming climate has made the western drought about 40 percent more severe, making it the region’s driest stretch since A.D. 800. And there’s a very strong chance the drought will continue through 2030.

“Not only is this drought continuing to chug along, it’s proceeding at as full-steam pace as it ever has been,” says Park Williams, a climate scientist at UCLA and an author of the new research.

Soil moisture is at historic lows

For millennia, the most certain climate truth of the U.S. West has been that conditions change. A pulse of wet months or years will turn mountainsides and valleys lush green, then just as certainly a dry stretch will parch the green to brown.

But understanding what controls that variability, and its relationship to climate change, is critically important to everyone living in the region's boom-bust water cycle.

Williams and his colleagues wanted to understand how intense the current drought has been compared to past events throughout the Southwest, from northern Mexico up to Idaho. In 2020, they published a study that examined 1,200 years of regional drought as recorded by the growth patterns of trees.

What WBS Pump Can Help?

Solar Irrigation

Gonnect WBS Solar Pump with Sprinkels, and you will get an automatical solar irrigation systems.

Livestock Watering

WBS has small power pump such as 210W 500W pump. Automatically start to work when powewr is enough. It can start to fee animals daytime. At night, the pump will rtop and rest.

Water Storage

WBS Soalr Pumps can help to get water from deep underground up to 300m. And you can stock the water into a tank.

What's Hot of WBS Pump?

WBS solar submersible pump Store Online DSS 3-inch solar screw pump main features are low power, low voltage and large head.

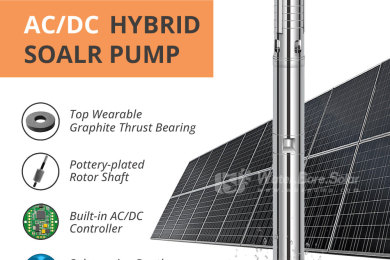

WBS 4 inch AC/DC Hybrid Solar Bore Pump for Irrigation, Farm, ranch. Factory direct sales. Wholesale Bulk Distributor.

WBS surface solar centrifugal pump for Irrigation and Household water, WBS SOLAR PUMP Store Online.

4 inch WBS AC/DC solar deep well pumps can not only run with DC solar power, also with electricity, generators.